A Summer Job At The Ansells Brewery, Aston, Birmingham, 1968 & 1969…

Ansells Brewery at Aston Cross became a non-taxable vacation job for me during two summers, 1968 and 1969. One of my father’s policy-holders from the Britannic Assurance Company was the Personnel Officer there and I was duly called up for an introductory interview, after a 6th form school year at KEGS Aston. I was under no illusion about my fate after the first real question: “Would you like to join the Union?” This of course meant I must join the Union, which I did of course, for there seemed no point in not doing so…

My only previous work experience had been a fortnight at my Auntie Ivy’s workplace when I was about 15. Larkin’s was a warehouse in Livery Street, Birmingham and I was a general worker, learning to wrap parcels ready for sending out by post. I answered telephones too, which was a novelty, as my parents didn’t have one at home. However, the brewery was a totally different kettle of fish…

There are some amazing images of the inside of the Ansells brewery online but they are copyrighted and I was unable to obtain permission to use a few of them to illustrate the types of work I have described below…

Maybe keep in mind the three words ‘health and safety’ as the article below unfolds…

I took the buses to work that I had used to get to school, for Ansells was at Aston Cross but of course I made my way home alone too, even though my father owned a car by that time.

|

| SALTLEY, WHERE I CAUGHT THE NUMBER 8 BUS TO ASTON CROSS, AFTER GETTING OFF THE 55 FROM SHARD END... |

Each employee was given ten beer tickets per week, each one exchangeable for a pint of beer in the canteen. However, by wheeling and dealing some guys drank much more than their individual allotted quota. I gave my tokens away but I was reminded of films which show prisoners trading cigarettes… Big Jerry, a rather huge Irish guy was thus reckoned to consume some twenty pints of beer a day at work and I didn’t doubt this for one moment.

While I was on the payroll he was caught going up on a lift with a crate full of Gold Label bottles and he was doubtless taking them off to be squirrelled away somewhere for his own consumption. He had been down to the stores and simply removed the booty. Already under threat of dismissal, Big Jerry’s future was amazingly secured by a solid defence from his Union. It was along the lines of the fact that he was simply ‘moving the crate’, although no reason was given for his action in a rather weak but accepted defensive strategy… Strangely, he used to drink M&B beer in his local pub at night… He told me that he used to consume ten or eleven more pints of ale each evening.

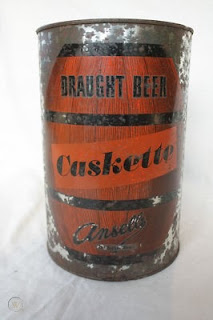

Those were the days when small metal caskettes were filled with Ansells beer and each one was plugged at the top by a rubber bung.

I was once put on a rotation system where we regularly moved round to a new position, rather like volleyball players do, but after forty or so mundane minutes in one area of the caskette filling section, I recall watching each of three bungers whipping a caskette off the rotating filling machine and slipping the flat-peaked, cap-shaped bung into its expectant hole. I was sure I would never learn this skill and I was right, at first…

In fact even the logistics were against left-handed me, for I would have to do this right-handed because of the positioning of the machine and the track. Heck… For fifteen minutes it was like I was bungling an activity in TV’s the ‘Generation Game’ but after half an hour or so, I began to bung in a more relaxed fashion. It became so smooth, so sweet and suddenly I felt like I was part of a real team.

I really enjoyed the job of stacking the caskettes in fours too, with one cardboard lid covering the tops of the cans and another being placed beneath the bottoms. They were then fastened by a black plastic binding, dispensed from a mechanical wrapping machine, operated by a team member.

I was actually forced to repair this machine so often during the days when I worked in that section, that I was regularly called away from another post to “Fuckin’ mend the bleedin’ thing…”

Er, me? Repair something? Really? I’d never even changed an electric plug in my life or even changed a light bulb at that point in my life but the malfunctioning machine seemed to like my attitude, somehow allowing me to adjust it with a view to ‘making do and mend’ and so I became au fait with mechanics for the first time in my life…

Rejected caskettes were treated brilliantly. They were given a good shake some distance from a bare wall, which was to act as a target. The bung would then be pulled and just like from a water cannon, the escaping beer flew like a jet from a firefighter’s hose. It shot with tremendous power against the wall and I just couldn’t believe my eyes… It was brilliant to fire this unique and powerful weapon…

I was once given a small glass of freshly made light ale from that caskette filler and I must admit that I have still never tasted beer so good . . .

I recall three nightmarish jobs within the old brewery too and the first was a day I endured of not rolling out the barrels but rolling over the barrels. This activity was no barrel of fun for the novice. The older, more obese wooden barrels and the newer metal kegs, all quite empty, needed moving along a difficult corridor with several corners, ready to be piled up. It seemed like it was never-ending, as one after the other was collected, rolled, swung upright and stacked.

Secondly, I recall a West Indies v England cricket game commentary blaring across the yard from a portable transistor radio. I was on a reception deck at the time with five or six others and we were treated like tenpin skittles by three or four West Indian guys who were unloading their trucks of empty casks and barrels onto the deck.

They loved the fact their famous West Indies bowlers Wes Hall and Charlie Griffith were playing havoc with England’s batters at the time and so they were in fine humour as they unloaded and goaded!

They would simply whip the empty barrels at us and took delight in deliberately aiming them at the legs of the waiting deck-men. Those vessels were still heavy and would have broken the legs of an unaware defender. It was a terrifying challenge to flick up the end of an approaching rolling, spinning barrel and bring it under control with gloved hands. Once only I took my eyes off a barrel and was forced to spring upwards and leap over the missile like in a mobile high jump event. I was lucky…

Thirdly, I was given an hour or so on an eye-killer. This was a chair, a metre or so from a conveyor belt carrying newly filled bottles of beer, all clinking and jittering shoulder to shoulder on their journey to be crated and then loaded onto lorries for distribution. The job was to train one’s eyes on a mark which showed the minimum level of beer allowed in each bottle. One was expected to pull out any short measures. Protective spectacles were provided but the strain on one’s eyes and the nauseous feeling inside were unbearable. Perhaps my eventual abhorrence at wearing protective glasses in Birmingham Museum’s dust had its roots at the brewery. Often, bottles exploded and glass splintered like shrapnel…

I stacked crates a lot though, which was great because after awkwardly handling the first few, one was able to pick up a rhythm and the job became quite a pleasant way of keeping fit. I hosed and then swept floors too but I guess I was being paid well and thus didn’t mind putting my back into the jobs given me.

Some of the dreadful women who worked on the factory floor would remain for much of the day on this task and all of them wore glasses either permanently or just for reading. In Holland apparently, people were only allowed to do this job for three hours in total per day, including several breaks.

Those women at Ansells were tough and often harsh, wearing their rather unpleasant blue nylon belted ‘housecoats’. One of them was nicknamed ‘Dirty Mary’, whilst another was reputed to have had sex on the factory floor with a guy beneath her. Apparently, she became so madly excited that she deposited excretion upon the disgusted chap and in front of several cheering spectators too. Nice…

I met an Asian guy whose permanent job was on the top floor of the brewery, working with the empty crates, which came up by conveyor-belts from the yard, after being unloaded by trucks. All he did was to remove them, stack them and deposit some of them onto another line, leading to the bottle-washing machine on the floor below. This was a machine I was to learn about soon afterwards.

I worked with the old chap eagerly, for he really was lovely but his English, at worst unintelligible, was at best disgusting. A sample sentence might contain four or five swear words, for those were the words he heard most often from the other chaps in the brewery. To communicate with him, I was forced to swear too, so he could get my meaning… This was a decent job though, just the two of us on the line.

Eventually, four smallish caskettes started to be packed into complete cardboard boxes, probably after those awkward rubber bungs had became redundant. During my second summer at the Brewery, I was on a line where the boxes were conveyed into a glueing section, almost like a tunnel on a railway-track. Typically, every now and again, the glue machine stuck (no pun intended) and boxes became jammed. The only way to correct the problem was to reach into the glueing section and force a box onward. Obviously, the conveyor line was turned off by push-button whilst obstructions were removed. Everyone present could observe all of this operation because the glueing section was clearly visible.

One day, two other students were working with me on the line and as usual, a box became twisted just inside the glueing tunnel. I hit the stop button and the belt, moving right to left, came to a juddering halt. I reached with my left arm into the opening of the section, pushing at the top of the box as I forced my hand between it and the framework of the machine. Unfortunately, one of the two students thoughtlessly reactivated the line, forced the free box on and my left arm went with it. My wrist was held like a vice and I was watching it disappear…

I yelled for the stop button to be pushed but the other student panicked and lost all sense of remedy, forcing an alerted guy to run from another line to rescue me. My forearm was shaped like a meandering river and I was rushed to a matron, where my injury was supported but luckily it was not broken and I was sent home.

I played goalie with my dad at the local recreation ground that evening and a small white scar still remains on the inside of my left wrist to this day.

One of my vivid memories of Ansells was the bottle-washing machine. I enjoyed those particular days I spent at one end of the factory floor with just two of us patrolling the line. A conveyor-belt brought crates of twenty-four empty bottles towards a wall where it cornered right and the crates began to queue, vibrating. Three or four of the crates were pulled into position for a mechanical set of tough, sharp plastic ‘hands’ to drop onto, thus removing the dirty bottles from the crates.

The ‘hands’ opened like two sharp plastic teeth, which jerked down onto the necks of the glass bottles, lifted them out and took them inwards, placing them onto a wide conveyor leading to a revolving drum, which then picked up the bottles it was being fed, like a seething creature waiting for mesmerised food to come its way, belching out steam.

Unfortunately, odd bottles jammed, broke or rolled about on the machine and it was always me who volunteered to leap onto the wide conveyor and clear up any mess. The first thing I asked about when I was introduced to this machine was the location of a stop and start button, which I’m glad I did…

I was working with a guy who was a very conscientious young man and was I think highly regarded by managers and colleagues alike. However, one particular crate created some difficulty and for some reason the two dozen ‘hands’ jammed some 15cm from the necks of the targeted bottles. As my working partner set about checking the problem, I suggested turning the machine off but he declined and he didn’t press the button, which was situated just a metre to his right.

In seconds, panic reigned. Suddenly and quite inexplicably, the framework holding those lethal-looking hands un-jammed themselves and jerked down onto my colleague’s hand, which was resting on the waiting crate. The sharp plastic edges cut into his knuckles and the back of his hand, close to the wrist. I reacted fast, dashing past him and quickly pressed the machine’s off, then tried to manipulate a lifting of the plastic grips, just to ease the pain. I had screamed for help too and with the aid of others, the offensive weapons were finally lifted away from the guy’s hand. His injury was nasty and I didn’t see him again that summer, leaving me to complete my week in this area as section leader! Unbelievable…

I can still smell the stale, unpleasant odour of those unwashed empty beer bottles.

I tend to consume little of the stuff these days…

Night working at the Holt Street brewery…

During my last summer at the brewery, I was asked to work a week of nights at the depot in Holt Street, near Woodcock Street swimming baths, now a part of the Aston University campus.

I travelled by bus to the facility at around 10.15pm, then of course made my way home at around 6am the following morning. No lifts for me, unsurprisingly. It was strange being at work in the darkness of Gosta Green, for whilst there it seemed that nobody else was awake at all…

I can’t recall more than a couple of others being on duty there during my week of work and I have vivid memories of a maze of pipes crossing the ceilings in different directions and the Caribbean guy in charge knew exactly which ones carried beer and which ones carried air, also which ones were used for suction and which ones were used for heating. Beer was stored in large swimming-pool type vessels on one of the upper floors and then after it had settled it would filter down to the floor below and then down again to another floor, until it was used to fill tankers waiting in the yard with their really well paid drivers.

I was involved in froth removing and container cleaning whilst working there, which was a remarkable experience. Using a wide rake/shovel on runners stretched across the deep vessel, froth was laboriously pushed to one end by two workers. A wide pipe was then inserted into the stacked up froth and it was sucked out, as if by a vacuum cleaner. This action was repeated as more froth appeared. It was strange to actually see several metres of froth piled up on beer and then to see it gradually disappear. I was able to take part in that activity, which was quite satisfying.…

When a vessel was empty, no-one was allowed to clean the inside of it until its killer fumes had dispersed. Brooms and water were eventually manhandled into the vessel and the walls were brushed from top to bottom. Then an acid spray was hosed around the walls and that meant suiting up in protective clothing. Clearly the acid was to kill any bacteria and germs left behind but then finally, a type of whitewash was brushed onto the walls, to make sure that every nook and cranny was immaculately clean.

It was hard work but not as messy or menacing as cleaning out the hop-vats. I did that just once and apart from shovelling out a smelly, squelching mass of residue in a sweaty metal vat, I had to hose it all down too and then wipe it clean. It was like mucking out a space capsule after a monkey’s hair-raising, shit-dumping mission.

I was told to take a shower immediately afterwards, then physically rest for one hour and read a newspaper… It was quite a strange set-up but I enjoyed my week there, for it was fairly relaxed for the most part with odd, sporadic rushes of activity and heavy work…

No comments:

Post a Comment